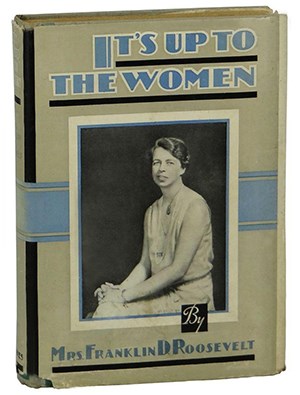

Throughout her long career in politics, Eleanor Roosevelt (ER) championed both women’s rights and women’s activism. ER believed that women were entitled to equal rights. But she also believed that women’s differences from men made them uniquely qualified to engage in political activism. As she put it in her 1933 call to action, It’s Up to the Women, “Women are different from men. They are equals in many ways, but they cannot refuse to acknowledge the differences.” 1 To ER’s way of thinking, women’s differences were the basis for women’s activism. As she explained in an interview with Good Housekeeping: “Women must become more conscious of themselves as women and of their ability to function as a group.” 2 In addition, ER believed that women’s distinctive approach to politics would benefit society as a whole. As she told the New York Times: “Women are by nature progressives.” 3 ER exemplified what scholars have described as the “domestication of politics,” engaging in a distinctive “women’s political culture” that placed women at the vanguard of progressive movements for human rights both at home and abroad. 4

“The fundamental purpose of feminism

is that women should have equal opportunity

and equal rights with every other citizen.”

Eleanor Roosevelt

woman suffrage movement — although she also did not publicly oppose woman suffrage. When a member of the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage attempted to gain her support, she demurred. Until the 1920s, ER “considered any stand at that time quite outside my field of work” as the mother of young children and the wife of a rising politician. 5

It was not until later in life that ER described herself as a feminist. In 1935, in an interview for Equal Rights, she asserted: “The fundamental purpose of feminism is that women should have equal opportunity and equal rights with every other citizen.” 6 But although ER did not engage in the suffrage movement and only belatedly claimed a feminist identity, her activities in the first two decades of the twentieth century laid the groundwork for a lifetime of feminist activism.

ER’s activities in these years exemplified social feminism, an understanding of women’s role that encouraged a broad cross-section of American women to engage in public life. In addition, ER’s commitment to the settlement house movement and her participation in social reform introduced her to suffrage activists who saw the vote as a vital tool to improve American society, especially for working women and their families. In the coming decades, these associations would become stronger still, transforming the former debutante into a political powerhouse.

[Women] began to realize that the one calling in which they were, as a body, proficient, that of housekeeping and homemaking, had its outdoor as well as its indoor application. . . . It was this knowledge, the extension of the homemaking instinct of women and the broadening out of the mother instinct . . . that led them out into paths of civic usefulness. 7

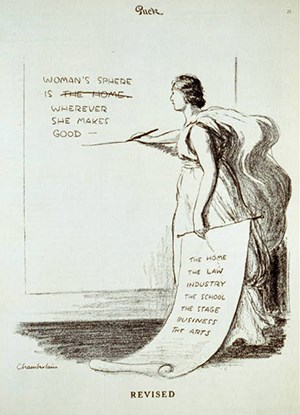

“Woman’s sphere,” previously narrowly defined, expanded to encompass virtually all aspects of daily life — or “wherever she makes good,” as a 1917 pro-suffrage drawing in Puck put it (see illustration above). Thus, while for the vast majority of nineteenth-century Americans, gender differences excluded women from the exercise of power, for a growing proportion of twentieth-century Americans, these differences necessitated women’s engagement in politics. The domestication of politics empowered women to become political activists. As ER put it, modifying her earlier views of politics: “In the old days men always said that politics was too rough-and-tumble a business for women, but that idea is gradually wearing away.” 8

For ER, the brief hiatus between school and marriage provided a powerful introduction to a distinctive women’s political culture. Educated in France, ER returned home to New York to make her formal debut in 1902. At age nineteen, she was “still haunted by my upbringing,” she later recalled, “and believed that what was known as New York Society was really important.” 9

Frances Perkins. But work in these organizations also introduced her to women with very different backgrounds, such as WTUL president Margaret Dreier Robins and the fiery Jewish labor organizer Rose Schneiderman. ER also joined the New York Women’s City Club, which she described as a “clearing house for civic ideals.” 12

ER’s activism in the 1920s also acquainted her with prominent pacifist feminists, such as Jane Addams, Lillian Wald, and Caroline O’Day. In the aftermath of the destruction of World War I, ER and her fellow pacifists urged the United States to join the fledgling League of Nations and the World Court to advance international cooperation and prevent future global conflicts.

Elizabeth Read, who became ER’s political tutor as well as her personal attorney, and her partner, journalist Esther Lape. Through Lape and Read, ER became acquainted with Mary W. Dewson and her partner, Polly Porter. In the 1930s, Dewson, a major player in the women’s division of the Democratic Party, would become one of ER’s most powerful political allies.

________________________________

Eleanor Roosevelt

ER’s immersion in New York’s reform milieu also introduced her to Marion Dickerman and Nancy Cook. Cook, a talented artist who was active in the Democratic party, and Dickerman, an educator with a social conscience, became ER’s closest companions in the mid-1920s. Together with Caroline O’Day, they formed the Val-Kill partnership, which grew to include the Women’s Democratic News, edited by ER, the Todhunter School, where Dickerman was principal and ER taught, and the Val-Kill furniture factory, managed by Cook. ER, Cook, and Dickerman also built a cottage for themselves on the Roosevelts’ upstate New York estate.

In the 1930s, ER built on the foundations of her New York feminist political community to facilitate the creation of a network of female politicos who helped shape domestic policy during the New Deal. This group included Mary W. Dewson, head of the Women’s Division of the Democratic National Committee; Frances Perkins, who became FDR’s Secretary of Labor; and Grace Abbott, Chief of the U.S. Children’s Bureau. For this group, the 1930s offered an unprecedented opportunity to translate women’s priorities into federal policy. As ER put it in December 1933, “there is nothing more exciting than building a new social order.” 15

Pauli Murray, who believed that Camp Jane Addams saved her life. In the years to come, ER’s relationship with Murray would strengthen her commitment to African American civil rights.

Throughout the 1930s, ER relied heavily on former journalist Lorena Hickok to serve as her eyes and ears. Assigned to cover ER during FDR’s presidential campaign, “Hick” became ER’s closest companion for many years. Her reports on rural poverty gave ER evidence to encourage FDR to expand anti-poverty programs, such as the experimental homesteading program near Morgantown, West Virginia, known as Arthurdale. Although Arthurdale was one of ER’s pet projects, it excluded African Americans, highlighting the shortcomings of the New Deal where racial equality was concerned.

ER also passionately advocated programs to support the arts, such as the Federal Theater Project, and to benefit young people, such as the National Youth Administration (NYA). The latter agency became a power base for the only Black woman in the New Deal network, educator and clubwoman Mary McLeod Bethune. Bethune’s friendship with ER desegregated the White House and strengthened ER’s commitment to civil rights.

The centerpiece of the New Deal was the 1935 Social Security Act, which laid the groundwork for a federal welfare state. With input from ER and other members of the women’s network, FDR proposed programs for federal aid to dependent children and federal support for public health agencies. Both programs were modeled on ones long championed by female reformers: state-level financial support for single women and their children, known as mothers’ pensions, and a pioneering maternal and child health care program, established under the Sheppard-Towner Act (1921-1929). The Social Security Act also included unemployment compensation and old age benefits.

________________________________

Eleanor Roosevelt

To deny any part of a population the opportunities for more enjoyment in life, for higher aspirations is a menace to the nation as a whole. . . . We must wipe out any feeling . . . of intolerance, of belief that any one group can go ahead alone. We all go ahead together, or we go down together.” 20

In keeping with these beliefs, throughout the 1930s, ER worked on behalf of African American rights and welfare. Working closely with Aubrey Williams and Mary McLeod Bethune in the National Youth Administration (NYA), she advocated expanding New Deal programs and insisted that Black Americans be included in them. She also collaborated with civil rights leaders in the American Youth Congress, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and the Southern Conference for Human Welfare to combat the poll tax, support a federal anti-lynching bill, and promote racial equality.

Leading by example, in 1938, when the Southern Conference for Human Welfare met in Birmingham, Alabama, ER refused to comply with local authorities’ insistence that she abide by local segregation statutes. When a police officer threatened to remove her from the seat she had selected alongside African American delegates, she moved her chair to the aisle between the white and Black sections. For the remainder of the four-day conference, she placed a folding chair in the middle of the room, refusing to sanction racial segregation. She also gave a stirring speech at the conference — which occurred just weeks after Kristallnacht, a night of unprecedented government-sanctioned violence against Jews in Germany — that highlighted the importance of the U.S. living up to the highest ideals of democracy at a time when human rights were endangered in Europe:

We are the leading democracy of the world and as such must prove to the world that democracy is possible and capable of living up to the principles upon which it was founded. The eyes of the world are upon us. 21

ER believed that a successful democracy was essential to counter the threat of fascism, and she regarded economic security as essential to national security. “If democracy is to survive,” she wrote in her “My Day” column in May 1940, “it must be because it meets the needs of the people.” 22 In her 1940 book, The Moral Basis of Democracy, she declared that “adequate education and adequate material security” were necessary to ensure citizens’ support for democratic government. 23

Indeed, ER’s efforts on behalf of African Americans often failed to achieve their objectives. For instance, in 1942, she joined civil rights leaders A. Philip Randolph, Mary McLeod Bethune, and Pauli Murray in a last-ditch effort to prevent the execution of Odell Waller, a Black sharecropper sentenced to death for killing his white landlord in self-defense. FDR rejected her repeated appeals to pardon Waller, who died in the electric chair. But ER remained determined to extend the promises of American democracy to all and optimistic about ultimate success. She reflected:

We have to live up to the traditions of our country as expressed in the Bill of Rights, in the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence even though I know in many cases we have fallen short. . . . I am far from giving up the problems of the Negro situation or any other. I am too old not to realize that lost causes usually are won in the end. 27

ER insisted that the best way to challenge fascism abroad was by strengthening democracy at home. In a “My Day” column published in November 1941—shortly before Pearl Harbor—she wrote:

If we cannot meet the challenge of fairness to our citizens of every nationality, of really believing in the Bill of Rights and making it a reality for all loyal American citizens, regardless of race, creed or color; if we cannot keep in check anti-semitism, anti-racial feelings as well as anti-religious feelings, then we will have removed from the world, the one real hope for the future on which all humanity must now rely. 28

After the U.S. entered the war, ER continued to press this point. “If we play our part with courage and clear-sightedness,” she predicted in her 1942 book, This Is America, “we may become the hope of the world.” 29

Universal Declaration of Human Rights would include not only political and civil rights, but also social and economic rights. As she put it, “You cannot talk civil rights to people who are hungry.” 30 After eight-five meetings, on December 10, 1948, the UN General Assembly approved the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. ER had succeeded in bringing her cherished commitment to comprehensive social welfare and universal civil rights to the international stage.

Back in the United States, ER continued to regard racial equality as an essential component of human rights. Civil rights were not merely a domestic issue, she argued, but “the question which may decide whether democracy or communism wins out in the world.” In 1950, she told Congress: “Our great struggle today is to prove to the world that democracy has more to offer than communism.” 31 In the 1950s, ER gave workshops for civil rights activists, encouraging boycotts and sit-ins and critiquing police repression of public protests.

If we do not see that equal opportunity, equal justice and equal treatment are [granted] to every citizen, the very basis on which this country can hope to survive with liberty and justice for all will be wiped away. 32

ER believed not only that the U.S. should be at the forefront of global efforts to promote democracy and protect human rights, but also that American women should lead the charge. Reflecting her longstanding support for both women’s rights and women’s activism, in 1962, the year of her death, ER chaired the Commission on the Status of Women, which called for women’s full participation in American life. Although ER was a latecomer to feminism, she fully embraced its commitment to protecting women’s interests, advancing women’s equality, and empowering women to promote social justice.

Anya Jabour, Ph.D.

Regents Professor of History

Director, Public History Program

Department of History

University of Montana.

This essay and web feature is made possible with funding provided by The Eleanor Roosevelt Val-Kill Partnership, Inc.